Madrid has some of the finest paintings in Western History to view. We recently visited the Prado and the Modern and Contemporary collection at Reina Sofia. Both were excellent but the painting that stood out for us was Picasso’s Guernica at the latter. Standing in wonderful isolation with two guards on either side it must be one of the most important paintings of the twentieth century. On the afternoon of 26th April 1937 around fifty Luftwaffe bombers dropped some 1500 kilos of bombs and incendiary devices, and the Italian fighter planes strafed the escaping citizens, destroying almost three quarters of the Basque town. An exercise in tyranny wielding its fist that resounds with today’s conflict in Europe.

Picasso was already working on his entry for the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris Exhibition of 1937 when news reached him of the Guernica raid. He laid aside his original project and worked on this painting to provoke and remind the world of the tragedy and atrocity. The huge picture is conceived as a giant poster, testimony to the horror that the Spanish Civil War was causing and a forewarning of what was to come in the Second World War. The horrors of war were to be delivered to civilians on an industrial scale.

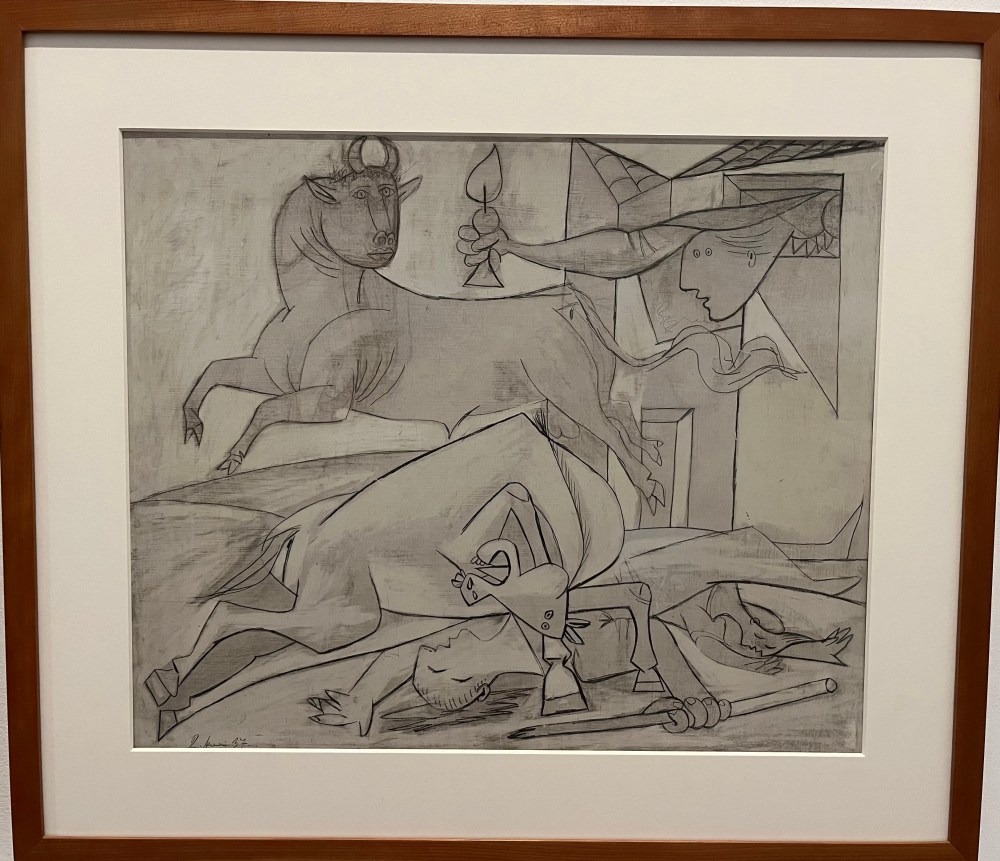

The painting does not refer directly to any of the scenes in Guernica but delivers, through its iconic motifs, a universal challenge to the futility and barbarity of war. The monochrome tones takes you by surprise when you first see it, and the power of the original motifs, which have never been fully described. There is a triangle of animals; the proud bull, the broken horse and the winged bird. Then there are numerous people; the dead soldier, the mother with her dead child, the woman in the burning building and the ‘pieta’ scene. The scale of the painting means you only see parts and the emotional movement takes you round the motifs in turn.

The government of the Spanish Republic acquired the mural Guernica from Picasso in 1937. When the Second World War broke out, the artist decided that the painting should remain in the custody of New York’s Museum of Modern Art for safekeeping until the conflict ended. This loan was extended for an indefinite period, until democracy had been restored to Spain, which happened in 1975. The work finally returned in 1981, to the Prado, and transferred to its current location in 1992.

We saw many iconic paintings in Madrid on our recent visit but for emotional value and connectivity with the current conflict in Ukraine this held the most powerful impact.