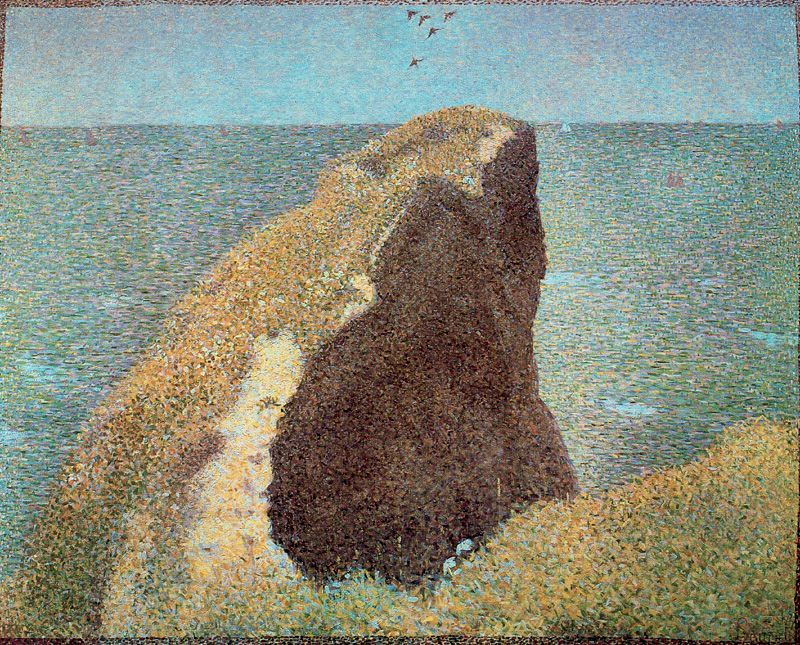

Georges Seurat was a giant in the modern history of European Art. A superb draughtsman, he was instrumental in bringing the curtain down on Impressionism and introducing new ways of thinking about painting using scientific calculation. He studied colour and instead of combining paint to produce different hues and tones he used pure colour and allowed our brains to do the work of mixing. By using small dots of pure colour we create the illusion of tone and hue in our brains. This acquired the name of pointillism, a term derided by Seurat and his followers. He was an anarchist through and through and any such analysis by the establishment he hated.

The National Gallery currently has a wonderful exhibition of Seurat’s work together with some of his followers and associates. Paul Signac was probably the most important of these carrying Seurat’s ideas forward beyond the pioneers untimely death at the Age of 31. It was Signac who after moving to St Tropez introduced the likes of Matisse and Picasso to the ideas of Modernism, heralding the great changes of the twenty First Century. Others include Van Goch, Pissarro, Toorop and numerous others.

The Neo-Impressionist collection of Helene Kröller-Müller is the subject of the exhibition at the National Gallery, entitled Radical Harmony. She was wife of a Dutch Industrialist and between between 1907 and 1923 put together amassed some 11,000 objects including the most significant group of neo-impressionist paintings. Within the collection is around ninety Van Gogh works, the largest holding outside the family. In order to keep the collection together and away from private hands the Kröller-Müller foundation donated the works to the Dutch state in 1935. Four years later the Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller opened its doors to the public to display the collection at Otterlo, near Arnhem, in The Netherlands

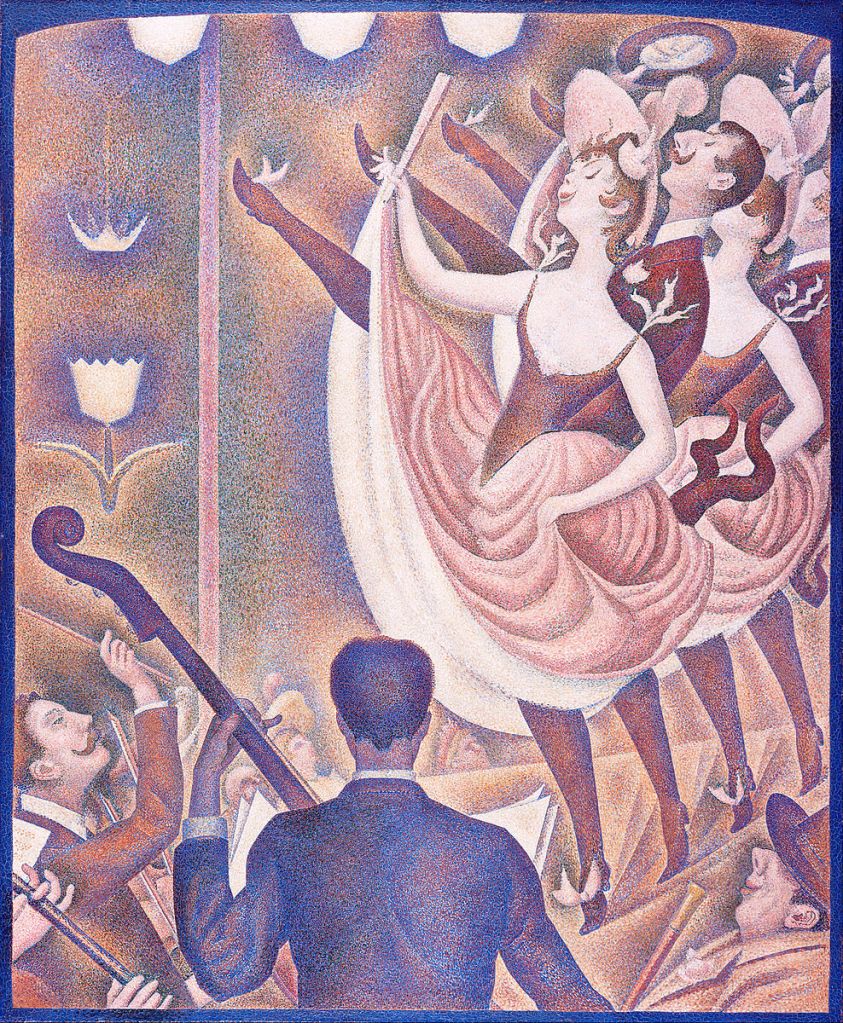

Probably the most important painting is Seurat’s Charut (1889-90) depicting a cafe scene with Can Can dancers and musicians. This large canvas dominates one of the rooms. Much of the remaining works are of a smaller scale and hint at Seurat’s anarchist ideas but also the juxtaposition with beauty. It is this riddle that the curator, Julian Domercq is trying to portray. The oxymoronic title, Radical Harmony, tries to reveal to us how the order of neo-impressionist painting style conceals the antiestablishment ideas in the background. By using pure colour on the canvas and allowing the viewer to interpret the painting was completely in opposition to the views of the authorities.

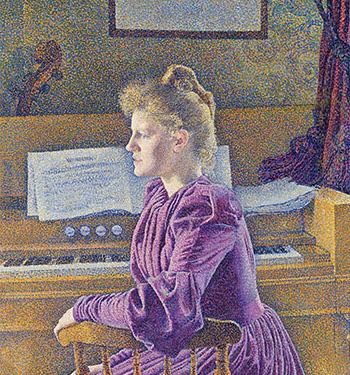

Domercq and the National Gallery have been reasonably successful in this but have fallen trap of the same riddle by trying to make every painting subject to this anarchist idea. The portraits are one of the areas where this fails. Like all artists throughout history they have had to paint commissioned portraits to earn money and stay alive and the neo-impressionists are no exception. There are some delightful portraits in the exhibition but there are two to look out for in particular; Maria Sèthe at the Harmonium (1891) and Maria van Rhysselberge-Mannam (1892) both by Théo van Rhysselberge (1892).

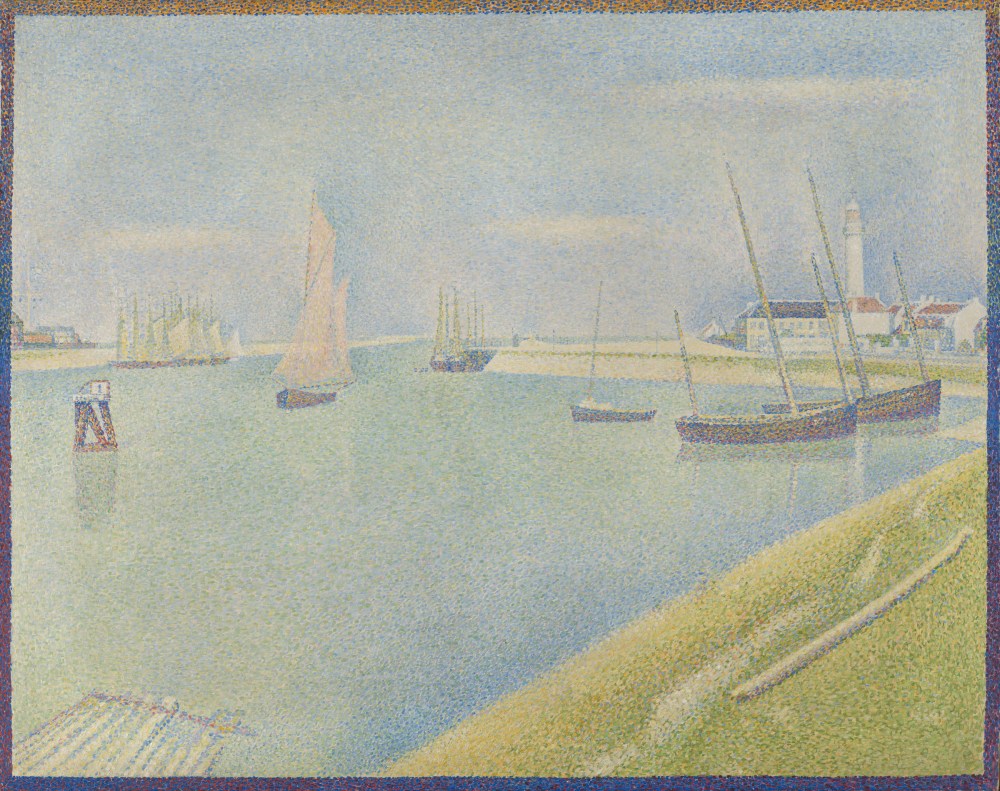

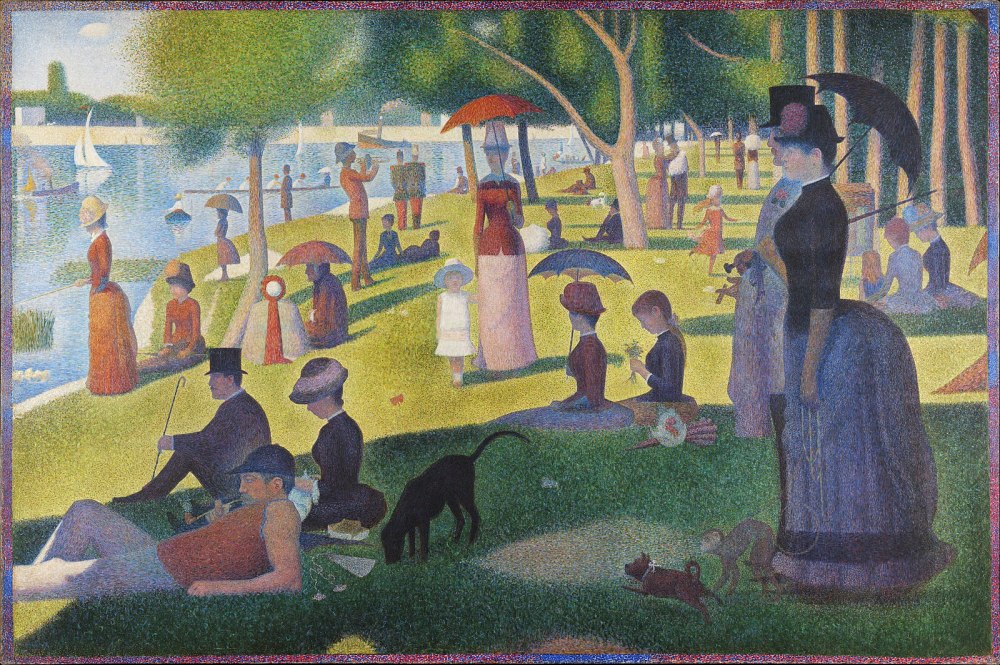

The exhibition is superbly set out in the newly refurbished Sainsbury’s Wing and a visual delight. While on the subject it would be remiss not to mention two of George’s Seurat’s huge masterpieces. His Sunday on La Grand Jatte (1894), in Chicago, which Kröller-Müller tried several times to purchase and Bathers at Asnières (1893) and, which is in the collection of the National Gallery. The former is an attack on the hypocrisy of the aristocratic class, with its hint of prostitution, and the latter attacking the same class against the background of the industrial world and the limitations of working class aspirations. You will find it as my painting of the Month in July 2020

Radical Harmony is at The National Gallery until February 8th 2026. Enjoy.